References

Abram P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al (2010) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 29: 213–40

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds (2017) Incontinence. International Continence Society, Bristol

Barrie M (2018) Respiratory conditions and urinary incontinence. J Community Nurs 32(1): 20–6

Battaglia S, Benfante A, Principe S, Basile L, Scichilone N (2019) Urinary incontinence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a common co-morbidity or a typical adverse effect. Drugs Aging 36(9): 799–806

Burge AT, Lee AL, Kein C, Button BM, Sherburn MS, Miller B, Holland AE (2017) Prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a questionnaire survey. J Physiother 103: 53–8

Button BM, Holland AE, Sherburn MS, Chase J, Wilson JW, Burge AT (2019) Prevalence, impact and specialised treatment of urinary incontinence in women with chronic lung disease. Physiotherapy 105: 114–19

Çolak Y, Nordestgaard BG, Laursen LC, Afzal S, Lange P, Dahl M (2017) Risk factors for chronic cough among 14,669 individuals from the general population. Chest 152(3): 563–73

Colley W (2020) Colley Model. Supporting the assessment of bladder symptoms in adults. Available online: www.continenceassessment.co.uk

Dorey G (2003) Clench it or drench it! A self-help guide for ladies who lunch, laugh and leak. Grace Dorey, Barnstaple

Haukeland-Parker S, Frisk B, Spruit MA, Stafne SN, Johannessen HH (2021) Treatment of urinary incontinence in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a randomised controlled study. Trials 22(1): 900

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al (2010) An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol 29: 4–20

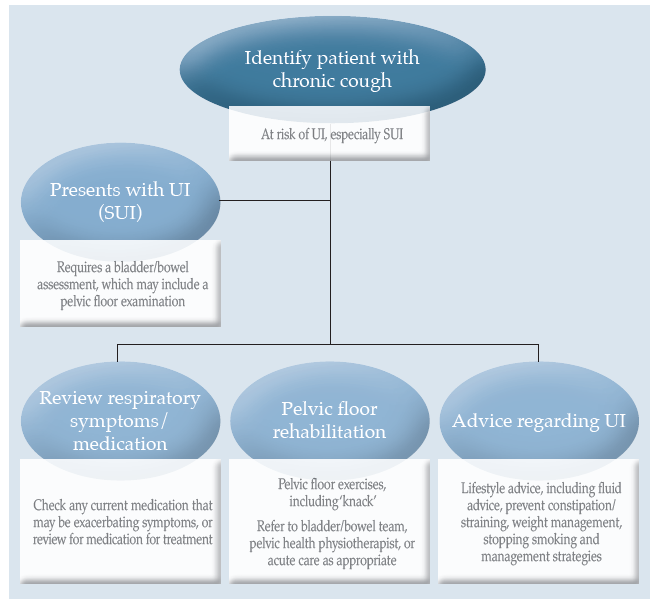

Hennessey S (2023) A urinary incontinence service for patients with chronic cough. Nurs Times 119: 4

Hongmei D, Cuiqui S, Xianghuai X, Li Y (2020) Drug-induced chronic cough and the possible mechanism of action. Ann Palliat Med 9(5): 3562–70

Mayo Clinic (2019) Chronic cough – symptoms and causes. Available online: www.mayoclinic.org>syc-20351575

NHS Inform Scotland (2023a) Cough. Available online: www.nhsinform.scot/illness-and-conditions/lung-and-airways/cough

NHS Inform Scotland (2023b) Why does COPD happen? Available online: www.nhsinform.scot/illness-and-conditions/lung-and-airways/copd/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary–disease

Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (2018) The Pelvic Floor Muscles: A Guide for Women. Available online: https://pogp.csp.org.uk/publications/pelvic-floor-muscle-exercise-women

Salman Q, Majeed R, Shafee I, Arif S, Waris M, Ayyub A (2022) Frequency of stress urinary incontinence with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in men; a cross sectional survey. Multicultural Education 8(12): 110–14

Yang C, Feng Z, Chen Z, et al (2022) The risk factors for urinary incontinence in female adults with chronic cough. BMC Pulm Med 22(1): 276

Yates A (2019a) Female pelvic floor 1: anatomy and pathophysiology. Nurs Times 115(5): 18–21

Yates A (2019b) Basic continence assessment: what community nurses should know. J Community Nurs 33(3): 52–5

Yates A (2019c) Female pelvic floor 2: assessment and rehabilitation. Nurs Times 115(6): 30–3

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds (2017) Incontinence. International Continence Society, Bristol

Barrie M (2018) Respiratory conditions and urinary incontinence. J Community Nurs 32(1): 20–6

Battaglia S, Benfante A, Principe S, Basile L, Scichilone N (2019) Urinary incontinence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a common co-morbidity or a typical adverse effect. Drugs Aging 36(9): 799–806

Burge AT, Lee AL, Kein C, Button BM, Sherburn MS, Miller B, Holland AE (2017) Prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a questionnaire survey. J Physiother 103: 53–8

Button BM, Holland AE, Sherburn MS, Chase J, Wilson JW, Burge AT (2019) Prevalence, impact and specialised treatment of urinary incontinence in women with chronic lung disease. Physiotherapy 105: 114–19

Çolak Y, Nordestgaard BG, Laursen LC, Afzal S, Lange P, Dahl M (2017) Risk factors for chronic cough among 14,669 individuals from the general population. Chest 152(3): 563–73

Colley W (2020) Colley Model. Supporting the assessment of bladder symptoms in adults. Available online: www.continenceassessment.co.uk

Dorey G (2003) Clench it or drench it! A self-help guide for ladies who lunch, laugh and leak. Grace Dorey, Barnstaple

Haukeland-Parker S, Frisk B, Spruit MA, Stafne SN, Johannessen HH (2021) Treatment of urinary incontinence in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a randomised controlled study. Trials 22(1): 900

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al (2010) An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol 29: 4–20

Hennessey S (2023) A urinary incontinence service for patients with chronic cough. Nurs Times 119: 4

Hongmei D, Cuiqui S, Xianghuai X, Li Y (2020) Drug-induced chronic cough and the possible mechanism of action. Ann Palliat Med 9(5): 3562–70

Mayo Clinic (2019) Chronic cough – symptoms and causes. Available online: www.mayoclinic.org>syc-20351575

NHS Inform Scotland (2023a) Cough. Available online: www.nhsinform.scot/illness-and-conditions/lung-and-airways/cough

NHS Inform Scotland (2023b) Why does COPD happen? Available online: www.nhsinform.scot/illness-and-conditions/lung-and-airways/copd/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary–disease

Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (2018) The Pelvic Floor Muscles: A Guide for Women. Available online: https://pogp.csp.org.uk/publications/pelvic-floor-muscle-exercise-women

Salman Q, Majeed R, Shafee I, Arif S, Waris M, Ayyub A (2022) Frequency of stress urinary incontinence with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in men; a cross sectional survey. Multicultural Education 8(12): 110–14

Yang C, Feng Z, Chen Z, et al (2022) The risk factors for urinary incontinence in female adults with chronic cough. BMC Pulm Med 22(1): 276

Yates A (2019a) Female pelvic floor 1: anatomy and pathophysiology. Nurs Times 115(5): 18–21

Yates A (2019b) Basic continence assessment: what community nurses should know. J Community Nurs 33(3): 52–5

Yates A (2019c) Female pelvic floor 2: assessment and rehabilitation. Nurs Times 115(6): 30–3

Success!

Success!