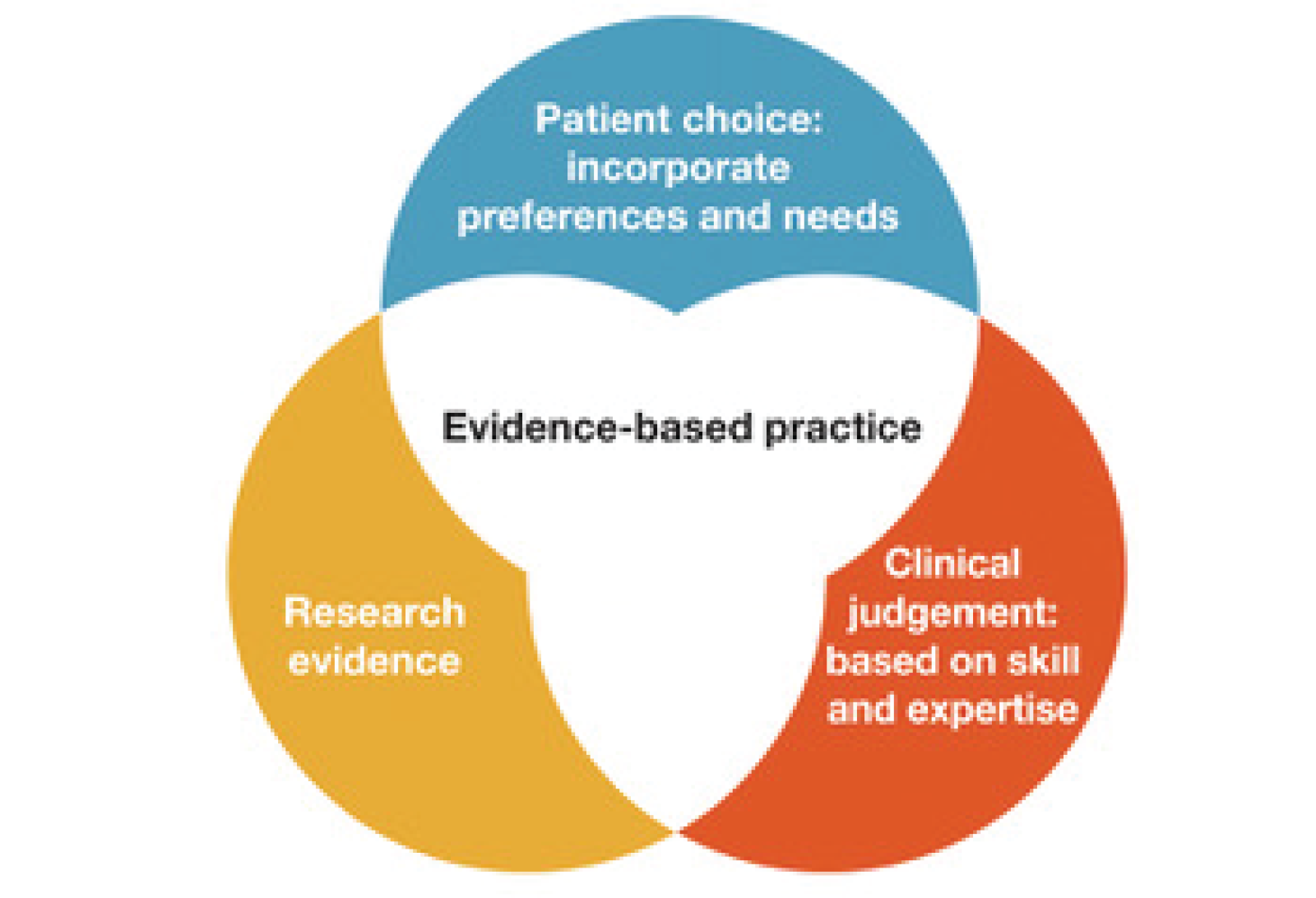

The three pillars of EBP

Let’s explore the three essential pillars of EBP:

Utilizing the best available evidence

The first pillar of EBP involves healthcare professionals (HCPs) seeking out and critically appraising the best available external clinical evidence, then applying it appropriately to clinical decision-making (Kerr and Rainey ,2021). Relevant evidence can come from a variety of sources, including systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized or non-experimental studies, qualitative research, expert opinions, descriptive studies, and case studies (LoBiondo-Wood et al, 2019). However, ndespite the level of evidence, it is not necessarily of equal quality. Poorly conducted research can lead to misinterpretation and have a negative impact on clinical practice (Greenhalgh, 2014). The volume and type of evidence that is produced can also be overwhelming (Greenhalgh 2014) and understanding evidence can be challenging. Therefore, it is essential for nurses to be able to identify high-quality, relevant studies and approach less robust or less applicable research with caution, especially in relation to the specific clinical context.

When considering evidence, you may ask yourself:

- Where do I begin?

- What sort of evidence is available?

- What is the difference in the types of evidence available?

- How do I know that the evidence is robust enough for me to change my practice?

- What happens if there is not enough evidence to support decision making?

Over the year, these questions will be explored in greater depth and answered as part of the EBP series.

Clinical judgement: combining clinical skills and expertise with the best evidence

The second pillar of EBP encourages the HCP , once they have critically appraised the evidence, to apply it appropriately to real patient scenarios (Greenhalgh, 2014). To effectively apply external evidence to individual patients, HCPs must possess expertise, knowledge, and skills, along with a level of proficiency and judgment that enables them to interpret and integrate relevant evidence into clinical practice (Greenhalgh, 2014).

Patient choice: Incorporating the patient’s unique experiences, needs, and circumstances into the decision-making process

The final pillar emphasises the importance of aligning individualised patient care with EBP by respecting each patient's values, morals, and circumstances. Healthcare professionals should be able to identify what matters most to the patient, discuss relevant options openly, and support shared decision-making, even when the chosen course of action does not fully align with the available evidence, or clinician preference.

These three pillars function collaboratively, as relying on any single pillar in isolation undermines the effectiveness of best-practice care. For instance, if clinical expertise or patients unique circumstances is solely driven by evidence, it can lead to suboptimal outcomes since even high-quality evidence may not be suitable for every individual patient.